Among the possessions that were donated by Emperor Otto I to the monastery of Bobbio with the diploma dated 25th July 972, there are the villas of Caperana (Capellana) and Rì (Ripus), on which both the coastal road and the one leading to Piacenza through the Sturla Valley and the Passo del Bocco converged; the latter, in particular, is dotted with Longobard posts and Bobbian possessions, while Longobard settlements can also be identified along a second road leading to Emilia through the Valleys Fontanabuona and Aveto from the Chiavarese territory. Next to the settlement of Bobbio-derived origin, in the area of Rì there was also a court belonging to the Church of Genoa; other ecclesiastical properties were located in the area of Caperana. On the heights of Maxena a considerable patrimony of land was concentrated, which was relevant to the Genoese Church.

The earliest mention of Sanguineto dates back to 1059. The church of San Pietro, already mentioned in documents from 1164, was located at the foot of the territory of Maxena; the church, which housed the Saint James hospital and overlooked the sea, was founded around the eleventh century.”.

The name “Chiavari” appears for the first time in a document dated 980 and a second time in an act of 1031, with which Tedisio, Count of Lavagna, received several goods on lease from the bishop of Genoa Landolfo, including some in Valle Clavari; these possessions would remain for centuries with his descendants.

In its expansion towards the Riviera, the Municipality of Genoa found strong resistance in the territory of the Counts of Lavagna, who were subjugated only by the middle of the 12th century; but this was not enough to defeat their power in the Tigullio area, where they were strongly rooted and enjoyed widespread support.

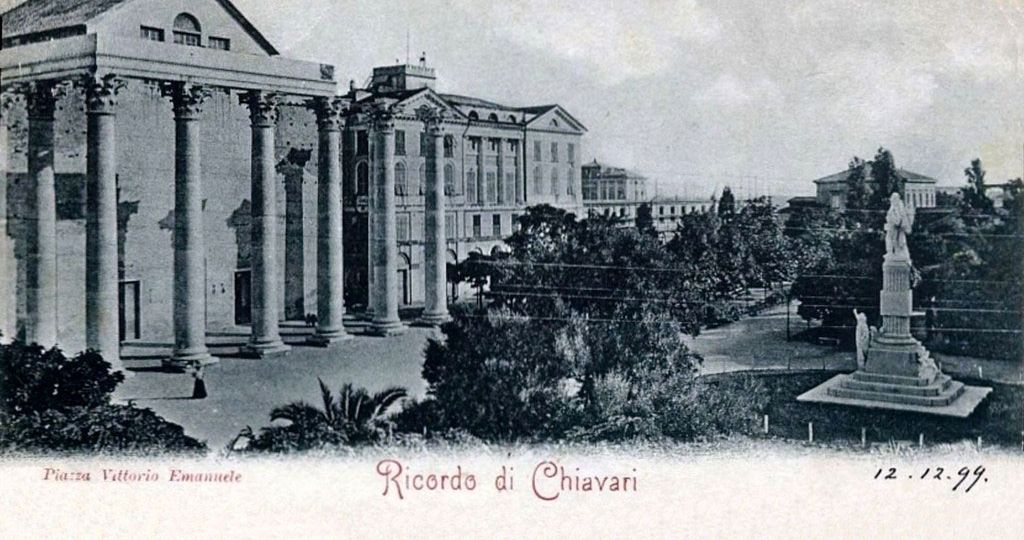

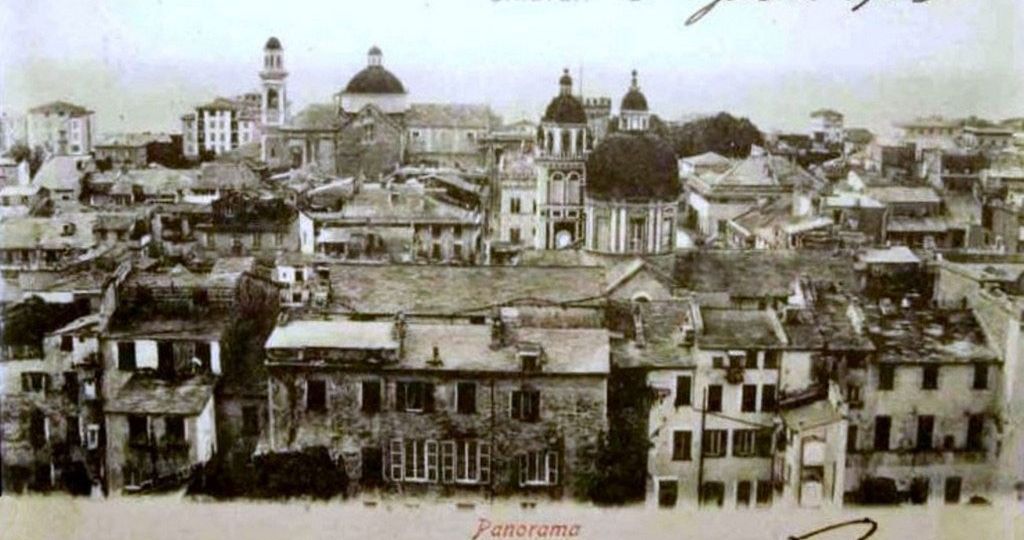

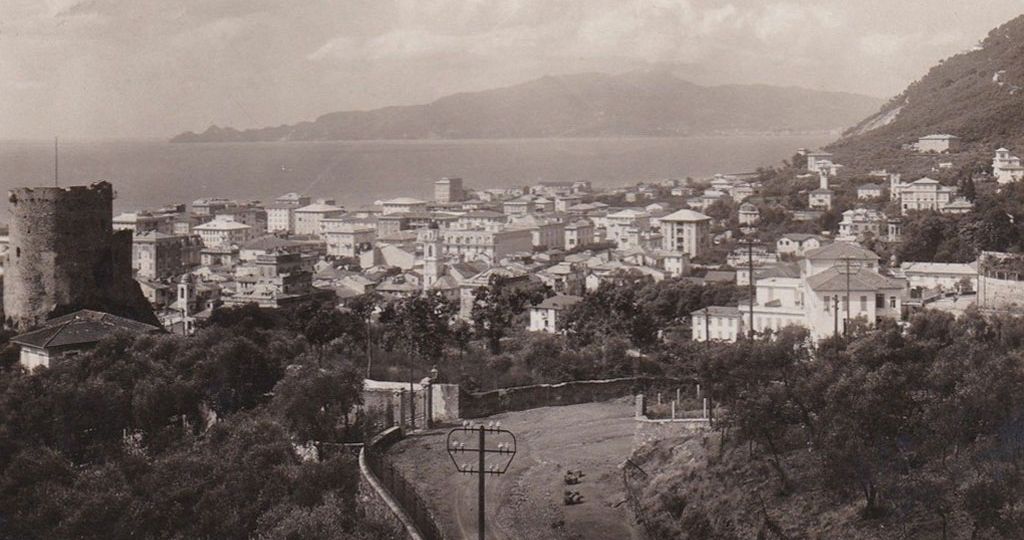

In 1167 the Genoese consuls decreed the erection of the castle of Chiavari, which would constitute a Genoese garrison on-site. Given the strong resistance of the Counts of Lavagna, in 1178 it was decided to create the village, according to a precise urban plan that provided for the creation of four building blocks delimited by roads, which are still today identifiable in the historical center. The Counts of Lavagna, however, found a way to establish a presence in Chiavari through civil settlements and ecclesiastical foundations.

The Fieschi and Ravaschieri, the major families that descended from the Comitato Lavagnese, maintained a prominent role in Chiavari throughout the Middle Ages up until the modern age, though they often clashed with the Rivarola family, which had always been on the opposite political front.

During the 18th century, Chiavari, like all the villages of the Ligurian Levant, began to enjoy increasing economic prosperity as well as social and cultural growth, with the formation of a new and powerful bourgeois class.

In April 1791, sponsored by Marquis Stefano Rivarola, governor of the city, the Economic Society was established in Chiavari by prominent personalities from the business class, the intellectual world, the nobility and the most open clergy of the city, modeled after the Società Patria per le Arti e le Manifatture, founded in Genoa in 1786 at the initiative of a group of enlightened aristocrats, including Duke Gerolamo Grimaldi.

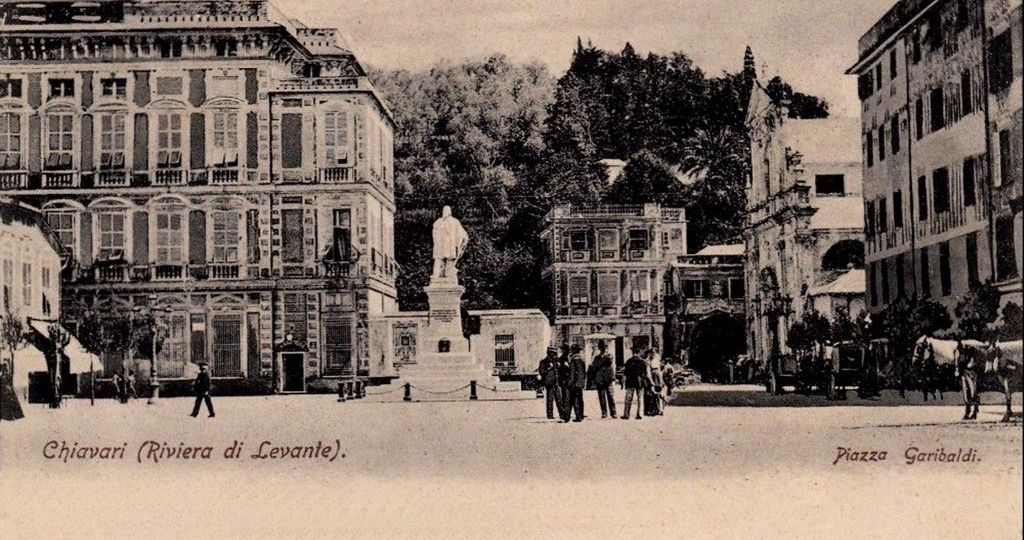

Chiavari experienced a particularly brilliant period during the Napoleonic period, when it was chosen as the capital of the Apennines and elevated to the rank of city by Napoleon Bonaparte .

The deep-rooted presence of Enlightenment ideas laid the foundation upon which Risorgimento thought was grafted, and found in Chiavari some of its authoritative exponents.

NOTABLE FIGURES OF CHIAVARI

Numerous figures from Chiavari distinguished themselves in various sectors over the centuries. In the next pages we will focus only on the biographies of some of them, born in Chiavari or descended from Chiavari families, who earned a prominent place in history due to the significance of their activities. This brief overview, however, bears witness to the extraordinary vitality of the Chiavari environment in the Modern Age.

Diego Argiroffo (1738-1800). A Franciscan friar, Argiroffo was part of the circle of Chiavarese intellectuals who enlivened the activities of the Società Economica. Father Diego’s opposition to Austria would cost him his life. After refusing to acclaim the Emperor, he was executed by the Austrians in 1800 on Mount Fasce, thus becoming the first political victim of the Austrians on Italian soil.

He wrote Memorie storiche e cronologiche della Città, Stato e Governo di Genova ricavate da più annalisti e scrittori, e autentici monumenti, sino ai tempi presenti dell’anno 1794-1799 [Historical and Chronological Memoirs of the City, State, and Government of Genoa from various annalists and writers, and authentic monuments, up to the present time of the years 1794-1799], which is carefully preserved in the University of Genoa’s Library.

Angelo Della Cella (1760-1837). He was born in Chiavari around 1760 but little is known about his life. Della Cella certainly absorbed the Enlightenment thought that spread in Chiavari at the end of the 18th century and due to his ideas, he was buried in unconsecrated ground after his death. He authored the ponderous work Memorie di Chiaveri [Memoirs of Chiavari, 3 volumes], which is kept in the Società Economica Library. The second volume in particular, titled Delle famiglie indigene, avventiccie, nobili, popolari, estinte e vigenti di Chiavari [About the indigenous, foreign, noble, common, extinct, and current families of Chiavari], which describes over six hundred local families, is an invaluable resource for genealogical studies.

Carlo Garibaldi (1756-1823). A versatile and original intellectual, Garibaldi was the most iconic figure of the Chiavarese Enlightenment movement. Born in 1756 in Prato di Pontori (now part of the Ne Municipality), Garibaldi earned his degree in Medicine at the University of Genoa in 1780; he then moved to Chiavari and began practicing his profession here, where he also nurtured his passion for history and genealogy, while actively engaging in civic and political affairs. In April 1791, he was among the founders of the Società Economica, where he held various positions. Garibaldi also contributed to the founding of the Accademia dei Filomati, which advocated for the establishment of a well-stocked public library. Garibaldi had strong pro-Jacobin sympathies and, after the proclamation of the Repubblica Ligure, he joined the new Central Administration of Chiavari; upon his proposal, streets and squares were renamed with names inspired by revolutionary ideals. The annexation of Liguria to the French Empire in 1805 marked his withdrawal from politics; the final years of his life were marked by bitterness and disappointment over the end of the revolutionary dream. Garibaldi wrote various historical and genealogical essays, such as the Alberi genealogici di famiglie di Chiavari [Genealogical trees of Chiavarese families]; his most famous work, though, is the repertoire Delle famiglie di Genova antiche e moderne, estinte e viventi, nobili e popolari [About the ancient and modern, extinct and living, noble and common families of Genoa], 3 volumes kept in the Società Economica Library. He also authored some studies on the Garibaldi family, preserved in the Archive of the parish of Sant’Antonio of Pontori.

Other people

Vincenzo Costaguta (1612-1660). His father Prospero occupied a prominent position in the city as a senator in Rome, an agent of the Republic of Genoa and the governor of the Confraternity of San Giovanni Battista de’ Genovesi; in 1645 the Pope appointed the Costaguta family as Marquises of Spicciano and Lords of Roccalvecce, in the Viterbo area. Vincenzo, a doctor of civil and canon law, moved from Chiavari to Rome during the pontificate of Innocent X; an apostolic protonotary and cardinal, he served as secretary of the Apostolic Chamber. In December 1655 he received Queen Christina of Sweden in Rome, with whom he would spend a long time discussing history, mathematics and music, subjects in which he was a profound expert.

Andrea Costaguta (1610-1670). A Carmelite friar and architect, in 1638 he was welcomed by Duchess Christina to the Savoy Court, where he was appointed advisor and theologian to Her Royal Highness. He was responsible for the design of the Santa Teresa complex of the Discalced Carmelites and other projects in the castles of Moncalieri and Valentino. Following an obscure event that occurred to him in his native Chiavari, in 1655 he was tried and relegated to the convent of Sassoferrato.

Agostino Rivarola (1758-1842). Brother of the diplomat Stefano Rivarola, he was apostolic protonotary at the conclave of Venice in 1800 and delegate to Perugia and Macerata. In 1808, he was taken prisoner by the French because he remained faithful to the Pope. As Governor of Rome, he was created cardinal in 1817 and, as legate in Ravenna, he led a campaign to repress the Carbonari sects, which culminated in a trial that, in 1825, saw over 500 members condemned. The following year he was the victim of an attack and, upon returning to Rome, was appointed prefect of Water and Roads.

Chiavari and its surroundings gave birth to many Italian Risorgimento political figures; Giuseppe Mazzini’s family came from Cogorno, while Giuseppe Garibaldi’s hailed from the area of Ne. We can’t help but mention also:

Davide Vaccà (1518-1607). According to tradition, Vaccà was born in the historical centre of Chiavari to an ancient local family. A doctor in Civil and Canon Law, Vaccà was a renowned jurist and personal friend of Andrea Doria. He served as Doge of Genoa for a two-year term between 1587 and 1589.

Stefano Rivarola (1755-1827). A member of a noble Chiavarese family, in 1783 Rivarola was ambassador of the Republic of Genoa at the court of Tsarina Catherine II, empress of Russia. Upon returning to Chiavari, he was appointed Governor of the city. During his tenure, he planned to implement a public lighting system based on the one he had admired in St. Petersburg.

In 1790, the area along the Caroggio Dritto [the main thoroughfare of the city] was illuminated by 19 lamps, making Chiavari one of the first cities to have a public lighting system. He was also one of the founders and first president of the Società Economica, and a supporter of the Chiavarina chair.

Stefano Castagnola (1825-1891). A law graduate from the University of Genoa, in his youth he formed friendships with fellow citizens Nino Bixio as well as Francesco Daneri, Goffredo Mameli, and Gerolamo Ramorino. In 1848 he volunteered with the 14th Bersaglieri Regiment and fought in the battles of Peschiera, Goito and Custoza.

Castagnola’s political career began in the municipal council of Chiavari and continued until his election in 1857 to the Subalpine Parliament, representing the 3rd Genoa district. Castagnola was a staunch supporter of Garibaldi’s Sicilian campaign. After the unification of Italy, he was first elected as a congressman for the Chiavari district (serving from 1861 to 1876) and later for the Albenga one. From 1869 to 1873, he served as Minister of Agriculture, Industry, and Commerce in the Lanza government. During the same administration, he also held interim roles as Minister of the Navy (1869-70) and Minister of Public Works (1871). In 1869, he was appointed senator of the Kingdom of Italy, and in 1888 he was elected Mayor of Genoa. During his tenure, he oversaw significant renovation projects in the Port of Genoa, organized the Columbian celebrations in 1892 and founded the Scuola Superiore Navale (Naval Polytechnic Institute). Castagnola served as President of the Società Economica during the 1871–72 term. He also lectured in Roman, Ecclesiastical, and Commercial Law at the University of Genoa.

Alessandro Bixio (1808-1865). As the elder brother of the famous Nino, Alessandro Bixio grew up in Paris at his godfather’s house, the sub-prefect of the Department of the Apennines. He became fully integrated into the Parisian political and cultural milieu and worked as an editor of the Revue de deux mondes, the most important French periodical of the 19th century. Elected as a congressman in the French Parliament, Bixio supported the armed intervention against the Repubblica Romana with the goal of restoring peace in Italy, which was being torn apart by revolutionary conflicts. Although Bixio was initially a conservative, he became a fervent republican activist. Following the coup of Louis Bonaparte in France in 1851, which paved the way for the establishment of a new Empire, he retired from political activism and turned to business, eventually becoming an important financier.

Gerolamo “Nino” Bixio (1821-1873). Born in Genoa to a Chiavarese family, Nino Bixio volunteered in the First War of Independence in 1848 and the following year took part in the defence of the Repubblica Romana. After spending some years in service on naval routes to South America, in 1859 Bixio took command of the Hunters of the Alps Battalion and became one of the organizers and supporters of the Expedition of the Thousand (Spedizione dei Mille). He fought and defeated the Bourbon troops in the battles of Calatafimi and Volturno.

Bixio possessed a strong-willed personality, which ultimately led him to become a key figure in the Bronte Massacre. The suppression of the revolt, led by Bixio himself, was intended to punish the crimes committed by local inhabitants upon hearing of Garibaldi’s arrival. In 1861, he was elected congressman in the Italian Parliament, where he demonstrated his extensive expertise in military and maritime sectors. In 1870, Bixio was appointed senator and supported general Cadorna during the decisive assault to conquer Rome. In the final years of his life, he revived his old passion for the sea and commanded a cargo ship he had designed himself, featuring a mixed sail and steam propulsion system. He died aboard this ship while en route to Indonesia.

Giovanni Antonio Mongiardini (1760-1841). A graduate in Medicine from the University of Pisa, in 1797 he embraced the Jacobin ideas that led to the formation of the Ligurian Democratic Republic. He became a member of the provisional government, the Police Committee and the Chemical Section of the Imperial Academy during the subsequent Napoleonic period. As a councillor of the municipality of Chiavari, Mongiardini became a member of the Legislative Corps of the Department of the Apennines. He was awarded the Legion of Honour for the services he rendered to the Napoleonic empire. Subsequently, Mongiardini continued to teach medicine at the University of Genoa, also publishing several works.

Bernardino Turio (1779-1854). A Chiavarese from the Rupinaro neighbourhood, Turio graduated in Pharmaceutical Chemistry from the University of Genoa. Afterwards, he dedicated himself to botany under the guidance of Prof. Domenico Viviani from Levanto. In 1806, as a young scholar, encouraged by the Chiavarese chemist and naturalist Antonio Mongiardini, he collected 640 plant samples from Sestri Levante, Rapallo, and the valleys of Aveto and Vara. These samples were later featured in a highly appreciated essay, deemed worthy of publication. Turio worked as a pharmacist in Chiavari while continuing his research in natural sciences and studied the sea algae of the Tigullio Gulf. However, due to a financial setback, Turio was forced to abandon his studies, which were later resumed by Giovanni Casaretto.

Giovanni Casaretto (1810-1879). A graduate in medicine, Casaretto experienced his first botanical observation in Odessa in 1836 alongside the naturalist De Verneuil. During his subsequent travels around the world with the zoologist Caffer (1838), Casaretto took refuge in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, where he conducted extensive field research and collected a significant number of botanical samples. These specimens were later sent to the University of Genoa. Casaretto’s botanical studies were published in the work Novarum stirpium brasiliensium decades, printed in Genoa between 1842 and 1845.

Federico Delpino (1833-1905). Born into a modest Chiavari family, the outstanding botanist was of delicate constitution. He spent his days outdoors, in a small garden adjacent to his home (today part of the Società Economica library). It was here that Federico Delpino conducted his first observations of nature, particularly focusing on the relationship between plants and insects.

Although he initially studied mathematics, he soon discovered his true calling during a trip to the East, where he had the opportunity to study exotic plant life. He then decided to pursue botanical research as a self-taught scholar and moved to Florence, where he divided his time between the botanical museum Orto dei Semplici (now Giardino dei Semplici) and the Libreria Webbian.

In 1865, his studies on the entomophilous fertilization of the Arauya albens earned him a place in the academic world as an assistant to Professor Parlatore, director of the Istituto Botanico of Florence.

Later, he held tenured positions at the University of Genoa and the University of Bologna; in 1893 he moved to Naples, where he passed away. His writings are the subject of studies and research to this day; particularly interesting is his correspondence with Darwin (kept at the Società Economica), in which Delpino – an advocate of rigorous scientific observation – expressed criticism of Darwin’s theory of pangenesis. Darwin himself wrote about the Chiavarese botanist: “many writers have criticized this hypothesis [pangenesis]; among them the most notable I knew is Prof. Federico Delpino, in his work Sulla darwiniana teoria della pangenesi (1869) [On the Darwinian Theory of Pangenesis]. He rejects the hypothesis I proposed, and I have greatly benefited from the criticisms he made on this matter…”

Michele Bancalari (1805-1864). A Piarist priest, he taught at the Collegio Nazareno in Rome, and later in Oneglia, Finale and Savona. In 1846, Bancalari secured a professorship in physics at the University of Genoa while continuing to serve as Provincial Superior of the Piarist order. He became renowned for discovering the diamagnetism of flames, a finding he presented at the 9th Congress of Italian Scientists in Venice in 1847. His theory was highly regarded by the famous physicist Michael Faraday, who built upon Bancalari’s findings one of his studies on the magnetic behaviour of gases.

Between the 19th and the 20th centuries, Chiavari had at least three professional ottonieri (brassworkers) specialising in the manufacture of scientific instruments: Egidio Caranza, Vittorio Ugobono, and Raimondo Isler.

Giuseppe Gaetano Descalzi (1767-1855). Descalzi was nicknamed “il Campanino” (in Italian campana means bell) because his grandfather was the bell ringer of the Church of Bacezza. He was the son of a cooper and craftsman and his work followed the Chiavari tradition of master cabinet makers (locally known as bancalari). At a very young age, in 1796, he was awarded a silver medal by the Società Economica of Chiavari for two wooden chests of drawers. In 1807, Marquis Stefano Rivarola, one of the founders of the Società Economica, invited the Chiavarese artisans to rework in a modern style some chairs he had brought from Paris; Descalzi responded to this invitation by creating a new and elegant design that simplified the decorative elements and lightened the structural elements; this marked the creation of the Chiavarina or Campanino chair.

Despite the fact that Descalzi’s production included a variety of products (he is credited with developing a new coating for wooden surfaces, incorporating slate into table inlays, and introducing a distinctive varnishing technique), his chairs gained renown among royal families of the time: from the Savoys to Francis of Bourbon, King of the Two Sicilies, Charles of Prussia and Napoleon III. The business was carried on by his family members: his sons Emanuele and Giacomo, as well as numerous grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Angelo Agostino Descalzi (1808-1876). An architect, maritime captain, and inventor. He was born in Chiavari and married a cousin of Giuseppe Mazzini’s mother. He sailed extensively, particularly towards South America, where he came into contact with the colonies of Ligurians established there. This gave him the opportunity to study maritime and fluvial currents worldwide, including in Europe. While in Italy, he focused on inventions (e.g., a floating dock) and design. Among Descalzi’s projects, some are impressive: the covering of the Bisagno River from Staglieno to the Foce district, and the reorganization and expansion of Genoa’s port, which earned the praise of Count Cavour. However, both the death of Count Cavour and his own passing hindered the implementation of the project.

Nicolò Descalzi (1801-1843). An explorer, astronomer, and hydrographer, Descalzi was the son of Giuseppe Gaetano Descalzi, known as “il Campanino” for being the creator of the Chiavari chair. In his early twenties, he moved to Buenos Aires, where he was appointed astronomer by the Argentine government and became the leader of an expedition aimed at opening a new communication route with Bolivia via the Bermejo River. The endeavour was only partially successful, as Descalzi was incarcerated due to his landing on the left bank of the Paraguay River, within the jurisdiction of the country of the same name. Subsequently, in 1834, Descalzi was appointed by the Argentine president as engineer, astronomer and hydrographer of the army for the expedition against the indigenous populations who were hindering the colonization of the Patagonia region. This mission gave him the opportunity to collect substantial geographic and astronomical information, as well as samples of rocks and minerals, plants and animals, and cartographic representations. These efforts earned Descalzi the title of Major in the Argentine military engineering corps, and a silver medal award. In the following years, Descalzi conducted further research, and in 1838, while conducting land surveys along the coasts of the Matanza River, he discovered fossils of Pliocene and Pleistocene herbivorous mammals, specifically the Megatherium Cuvieri and the Glyptodon Clavipes. He later donated these fossils to the Museum of Turin.

Giambattista Scala (1817-1876). A maritime captain and explorer, Scala travelled across Africa and South America, where he became aware of the tragic story of the slave trade. While in Lagos, he dedicated himself to replacing human trafficking with the trade of local products (rum, palm oil, and handcrafted items), making the city an important trading centre. For his efforts Cavour appointed him as a Consul of the Kingdom of Sardinia. Scala continued his explorations in the Niger area and reached Abeokuta, where the local king requested him to establish a farm and implement a business model similar to Lagos’s, in order to counter the slave trade. During his stay in the Kingdom of Orobu, he discovered the plant that produced vegetable sago, which was commercialised for making ointments, candles, and soap. In 1862, Scala published his travel memoirs in Genoa.

Antonio Oneto (1826-1885). As a master mariner, Oneto sailed for several years until, in 1868, he arrived in America, where he founded a shipping company using steamships for maritime transportation. However, the venture was unsuccessful, and he turned to the study of geography, exploration, and research. He focused his explorations on the Patagonia region, where he founded the city of Puerto Deseado. A peak in the Sarmiento colony was also named in his honour.

Enrico Millo di Casalgiate (1865-1930). Born in Chiavari, in what is now Palazzo Rocca, which at the time housed the subprefecture office under the authority of his father. At a very young age, he joined the army: when he was only 14, Millo enlisted in the Royal Navy, where he had a brilliant career. He is famous for the Battle of the Dardanelles during the Italo-Turkish War: on July 18, 1912, Captain Millo, commanding five torpedo boats, penetrated 15 miles into the Dardanelles Strait, which was controlled by the Turks, and was awarded the Gold Medal for Military Valour.

The following year he was appointed Minister of the Navy under the Giolitti government, a position he also held during the Salandra government. Governor of Dalmatia in 1918, Enrico Millo was appointed President of the Superior Council of the Navy in 1921, a position he held until 1923 when he retired with the rank of admiral.

Nicola Giuseppe Dallorso (1876-1954). At a very young age, when he was just 15, Dallorso was employed by the Banco di Sconto del Circondario di Chiavari (Discount Bank of the Chiavari District). By the age of 29, he was appointed general manager of the bank, increasing both its turnover and the number of its branches. In 1921, the credit institute changed its name to Banco di Chiavari e della Riviera Ligure (Bank of Chiavari and the Ligurian Riviera) enhancing its central role in supporting the Ligurian economy. In 1939, Dallorso was appointed senator of the Kingdom and awarded the Order of Merit for Labour.

Umberto Vittorio Cavassa (1890-1972). Cavassa’s origins were from Massa, and he moved to Chiavari with his family in 1902. He worked as an editor for the Roman newspaper Il Giornale d’Italia, and in 1928, he joined the Lavoro newspaper in Genoa, where he was appointed editor-in-chief in 1943. After World War II, he became the editor-in-chief of Secolo Liberale (later Secolo XIX), a position he held until 1968. Cavassa is also known for his career as a novelist, which he began in the early 1920s. Among his works: I Giorni di Casimiro (1948) and Gente Diversa (1956), set respectively in Chiavari and 19th-century Sanremo, as well as La Gloria che Passò (1961), a historical novel set in Chiavari during the Napoleonic Empire.